Where Does the Money Go After the Auction Sale? How Foreclosure Auction Bids Pay Off Liens

One of the most common questions we get from investors and homeowners alike is deceptively simple: when a property sells at a foreclosure auction, where does the money actually go? The answer matters enormously whether you are the person placing the winning bid, a junior lienholder hoping to recover your debt, or a former homeowner wondering if there is anything left for you after the dust settles.

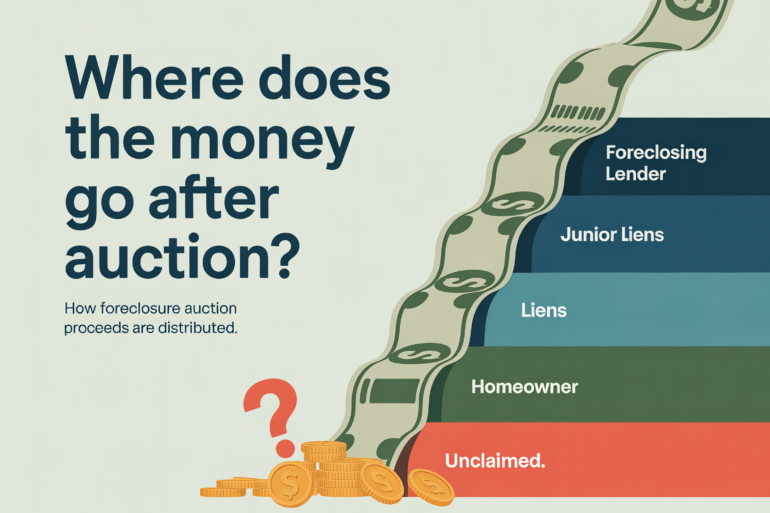

The short version is that foreclosure auction proceeds flow through a strict priority system, like water running downhill. The foreclosing lender gets paid first. Then junior lienholders line up for whatever is left. And only after every creditor in the chain has been satisfied does the former homeowner have a shot at any remaining funds. But the details of how this works, which liens survive the sale, what happens when a second mortgage is foreclosing instead of the first, and what the court does with leftover money, are where most people get confused and where investors who understand the system gain their edge.

This article breaks down the entire process, from the moment the gavel falls to the final disposition of every dollar. It also covers one of the most fascinating and least discussed corners of the Florida real estate world: the millions of dollars in surplus funds that sit unclaimed in county clerk offices and state accounts, and the cottage industry that has grown up around helping people recover that money.

In this article

The Waterfall: How Auction Proceeds Are Distributed

Think of foreclosure auction proceeds as a waterfall. The money starts at the top with the foreclosing lender and cascades down through each layer of creditors until it either runs out or reaches the former homeowner at the bottom. This priority system is not optional or negotiable. It is established by Florida law and enforced by the court.

The first entity to be paid from the auction proceeds is always the party that brought the foreclosure action. This is the plaintiff, typically the holder of the first mortgage. The final judgment of foreclosure specifies the exact amount owed to the plaintiff, which includes the remaining principal balance on the loan, all accrued interest, late fees, attorney’s fees, court costs, and any amounts the lender advanced for property taxes or insurance to protect its collateral. That full judgment amount is paid first, before anyone else receives a dime.

If the winning bid exceeds the judgment amount, the excess money does not go to the winning bidder and it does not go straight to the former homeowner. Instead, it becomes what Florida law calls “surplus funds.” Under Florida Statute 45.032, the court holds this surplus and distributes it according to a specific priority. The next parties in line are the subordinate lienholders: any creditor who held a recorded lien against the property that was junior to the foreclosing lender’s lien. This includes second mortgages, home equity lines of credit, judgment liens, HOA assessment liens, condominium association liens, construction liens, and even recorded tax warrants. Each of these subordinate lienholders has the right to file a claim for the surplus funds within the timeframe prescribed by the statute.

Only after every subordinate lienholder has been paid in full (or has failed to file a timely claim) does the former homeowner become entitled to whatever remains. The statute establishes a “rebuttable legal presumption” that the owner of record on the date the lis pendens was filed is the person entitled to the surplus after subordinate lienholders have been satisfied. In plain English, the homeowner is last in line, and they only get what is left after the waterfall has finished flowing through every creditor above them.

First Mortgage vs. Second Mortgage Foreclosure: Why It Changes Everything

This is the question that trips up more new investors than almost any other, and it came directly from one of our readers: if the plaintiff bids up to the combined balance of both mortgages, does the winning bid satisfy both? The answer depends entirely on which mortgage is doing the foreclosing.

When the first mortgage forecloses, its lien is the one being enforced through the sale. All junior liens, including the second mortgage, are extinguished by the foreclosure sale. The second mortgage holder loses their lien on the property entirely. However, they do not necessarily lose their money. If the auction price exceeds the first mortgage judgment amount, the second mortgage holder can file a claim against the surplus funds. If there is enough surplus to cover their balance, they get paid in full. If the surplus is less than what they are owed, they receive whatever is available and may still pursue the borrower personally for the remaining deficiency, but their lien against the property is gone.

The scenario changes dramatically when the second mortgage is the one foreclosing. In this situation, only the second mortgage lien is being enforced. The first mortgage, which holds senior priority because it was recorded first, is not affected by the junior lien’s foreclosure at all. The first mortgage survives the sale and remains attached to the property. This means the winning bidder at a second mortgage foreclosure auction acquires the property subject to the full remaining balance of the first mortgage. If you bid $50,000 at auction and the property still carries a $200,000 first mortgage, you now own a property with a $200,000 debt still owed to the senior lender. The first mortgage holder retains the full right to foreclose on their lien if that debt is not serviced.

This distinction is critically important for auction investors. Before placing a bid at any foreclosure auction, you must determine which lien is being foreclosed. Read the final judgment, review the complaint, and search the title to confirm the priority of the lien. A property that looks like a steal at a second mortgage foreclosure can turn into a financial disaster if you do not account for the surviving first mortgage. Conversely, a first mortgage foreclosure can be a clean acquisition because all junior liens are wiped out, giving you a clearer title.

A Practical Example of How the Money Flows

Let’s walk through a concrete scenario to make this tangible. Imagine a property in Orange County, Florida, with the following debts recorded against it: a first mortgage with a remaining balance of $180,000, a second mortgage (home equity line of credit) with a balance of $35,000, an HOA assessment lien of $4,500, and a judgment lien from a credit card lawsuit for $8,200. The property’s market value is approximately $280,000.

The first mortgage holder files for foreclosure. The final judgment is entered for $192,000, which includes the $180,000 principal plus interest, fees, and costs. The property goes to auction and the winning bid is $255,000. Here is how the money flows. The first $192,000 goes directly to the first mortgage holder to satisfy their judgment. That leaves $63,000 in surplus funds held by the court. The second mortgage holder files a claim for their $35,000 balance. The court approves it, reducing the surplus to $28,000. The HOA files a claim for its $4,500 assessment lien. Approved. The surplus drops to $23,500. The judgment creditor from the credit card lawsuit files a claim for $8,200. Approved. The surplus is now $15,300. The former homeowner, as the owner of record at the time of the lis pendens, is entitled to the remaining $15,300.

Now consider the same property, but this time the second mortgage holder is the one foreclosing. The second mortgage files suit, and the final judgment is $38,500 (their $35,000 balance plus fees). The property goes to auction. A winning bidder pays $50,000. That $38,500 goes to the second mortgage holder. The remaining $11,500 is surplus. The HOA and judgment creditor can file claims. But here is the key difference: the first mortgage of $180,000 is not paid from the auction proceeds. It survives the sale entirely. The winning bidder now owns the property subject to that $180,000 first mortgage. Despite paying $50,000 at auction, the bidder’s total cost basis is effectively $230,000 ($50,000 plus the $180,000 they now owe or must negotiate with the senior lender).

The Surplus Funds Process Under Florida Law

The handling of surplus funds in Florida is governed by Florida Statute 45.032, which lays out a detailed process for how excess auction proceeds are held, claimed, and ultimately distributed. Understanding this process matters for every party involved: investors who want to know how their bid will be applied, lienholders who need to protect their claims, and former homeowners who may be entitled to money they don’t even know exists.

After the foreclosure sale is completed and the Clerk of Court issues a certificate of disbursements, the clerk holds any surplus funds and the clock starts ticking. Subordinate lienholders and the owner of record have a limited window to file their claims with the court. Under the current version of the statute, all claims must be filed before the clerk reports the funds as unclaimed. The statute specifically defines a subordinate lienholder as “the holder of a subordinate lien shown on the face of the pleadings as an encumbrance on the property,” which includes second mortgages, judgment liens, tax warrants, assessment liens, and construction liens.

If the owner of record files a claim and there are no subordinate lienholders, the process is relatively straightforward. The court orders the clerk to deduct any applicable service charges and pay the remainder to the owner. The statute even provides a standard claim form that homeowners can use. Importantly, the form includes a bold statement that the owner does not need a lawyer or any other representative and does not have to assign their rights to anyone else to claim the money.

When multiple parties file claims, things get more complex. The court schedules an evidentiary hearing to determine the priority and validity of each claim. Subordinate lienholders must demonstrate the priority of their lien, its recording date, and the amount owed. The court then distributes the surplus according to lien priority, and whatever remains after all valid claims have been paid goes to the owner of record.

What Happens When Nobody Claims the Money

Here is where the story gets both troubling and, for some entrepreneurs, very interesting. A significant portion of foreclosure surplus funds are never claimed. The former homeowner may have moved out of state, may not know the funds exist, may not understand how to file a claim, or may simply be so overwhelmed by the stress of losing their home that dealing with court paperwork is the last thing on their mind. Subordinate lienholders sometimes fail to file claims as well, particularly when the lienholder is a large institution managing thousands of accounts and the surplus amount is relatively small.

Under Florida law, the path for unclaimed surplus is clearly defined. If no claim is filed within the initial period, the clerk is supposed to appoint a surplus trustee from a list of qualified trustees certified by the Department of Financial Services under Florida Statute 45.034. The surplus trustee’s primary duty is to locate the owner of record within one year of appointment. If the trustee succeeds, they file a petition with the court on behalf of the owner seeking disbursement. The trustee is compensated from the surplus itself: a 2% cost advance upon appointment and a 10% service charge upon successful disbursement to the owner.

If the surplus trustee cannot locate the owner within one year, the appointment terminates. At that point, the clerk treats the remaining funds as unclaimed property and deposits them with the Florida Chief Financial Officer (CFO) pursuant to Chapter 717 of the Florida Statutes, which governs the disposition of unclaimed property. The Florida CFO currently holds over $2 billion in unclaimed property of all types. Until claimed, the money is deposited into the state school fund and used for public education. There is no statute of limitations on claiming this money. An owner or heir can file a claim at any time through the state’s FLTreasureHunt.gov website.

Many individual county clerks also maintain their own lists of surplus funds that have not yet been sent to the state. For example, Marion County’s Clerk of Court publishes a downloadable Tax Deeds Surplus Funds List and Stale Dated Checks/Unclaimed Funds List. Lee County’s Clerk does the same, and most of Florida’s 67 county clerks offer similar public records. These lists are gold mines of information for anyone interested in the surplus recovery business.

The Surplus Recovery Business: A Whole Industry Hiding in Plain Sight

This brings us to one of the most fascinating side businesses in the world of Florida real estate, and one that most investors have never heard of: surplus funds recovery. The concept is simple. Millions of dollars in foreclosure auction proceeds are sitting unclaimed in county clerk accounts and state unclaimed property databases across Florida. The former homeowners who are legally entitled to that money often have no idea it exists. A growing number of entrepreneurs and companies have built profitable businesses around locating those homeowners, notifying them of their unclaimed funds, and helping them navigate the claims process in exchange for a fee.

The business model works like this. You start by identifying foreclosure cases that resulted in surplus funds. This information is publicly available through county clerk websites, court records, and the state’s unclaimed property database. You cross-reference the case information with the owner of record at the time of the lis pendens filing to find the person legally entitled to the funds. Then you track down that person, often through skip-tracing techniques, public records searches, or simply direct mail, and offer to help them recover their money.

Florida law explicitly allows this practice but regulates it to protect consumers. Under Florida Statute 45.033, a person can acquire the rights to surplus funds through a valid assignment from the owner of record, but the total compensation paid or payable to the assignee cannot exceed 12% of the surplus. The assignment must include a statement that the owner does not need a lawyer or any other representative to recover the funds on their own, ensuring that the homeowner is making an informed decision. Additionally, the state’s Division of Unclaimed Property allows registered claimant’s representatives (licensed private investigators, CPAs, and attorneys) to help people recover funds from the state database for a fee.

The opportunity is significant. Consider Florida’s foreclosure volume: the state recorded over 34,000 foreclosure starts in 2025 alone, according to ATTOM’s foreclosure data. Even if only a fraction of those result in surplus funds, and even if the average surplus is relatively modest, the total pool of unclaimed money across all 67 counties is substantial. Companies specializing in this field have reported recovering millions of dollars for former homeowners, with some individual cases yielding $40,000, $60,000, or more.

For real estate investors, the surplus recovery business offers an interesting complement to traditional auction investing. It does not require large amounts of capital, it does not require you to take possession of a property, and it leverages many of the same research skills (court records, title searches, skip tracing) that auction investors already use. Some investors run it as a standalone business, while others treat it as a side income stream that they pursue between deals.

How to Get Started in Surplus Recovery

If the surplus recovery business sounds appealing, here is a practical overview of how to get started. The first step is to identify cases with surplus funds. Start with your local county clerk’s website. Many Florida clerks publish surplus fund lists directly on their sites. You can also search the court docket for recent foreclosure cases and look for certificates of disbursement that show surplus amounts. The state’s unclaimed property database at FLTreasureHunt.gov is another source, though funds that have already been sent to the state may have different recovery procedures and fee structures.

Next, identify the owner of record. This is the person or entity listed as the property owner on the date the lis pendens was filed. You can find this information in the foreclosure complaint, the lis pendens itself, or through the county Property Appraiser’s records. Once you have a name, you need to find the person. Many former homeowners have moved, sometimes out of state. Skip-tracing tools, public records databases, social media, and good old-fashioned research can help you locate them.

When you make contact, transparency is essential. You need to explain clearly that the person has surplus funds available, that they have the right to claim the money on their own without paying anyone, and that you are offering to handle the process for them in exchange for a fee. Florida’s statutes are designed to protect homeowners from being taken advantage of during a vulnerable time, and operating ethically within those guardrails is not just a legal requirement but a smart long-term business strategy. Your reputation in this space matters, and word-of-mouth referrals from satisfied clients can become your most valuable marketing channel.

The actual claims process involves preparing and filing the appropriate paperwork with the court (or the Department of Financial Services if the funds have been sent to the state), providing proof of the owner’s identity and entitlement, and, if there are competing claims from subordinate lienholders, navigating the evidentiary hearing process. Working with a real estate attorney, particularly for your first several cases, is highly recommended. Many surplus recovery businesses partner with attorneys who handle the court filings while the recovery company handles the research and outreach.

What Auction Bidders Should Take Away From All of This

Whether you are bidding at a foreclosure auction, evaluating the potential profitability of a deal, or considering the surplus recovery business as an income stream, understanding how auction money flows is foundational knowledge. Every dollar has a destination, and the priority system that determines those destinations is set by law, not by negotiation.

For bidders, the most critical takeaway is to always know which lien is being foreclosed and what liens will survive the sale. A first mortgage foreclosure wipes the slate cleaner than a second mortgage foreclosure, but even first mortgage sales can leave you with surviving government liens or special assessments. Use platforms like PropertyOnion.com to identify upcoming auctions, research the properties, and pull together the lien information you need before the sale date. The few hours you spend on due diligence can save you from purchasing a property with obligations you did not anticipate.

For former homeowners, the most important message is this: if your property sold at a foreclosure auction for more than what was owed on the foreclosing lender’s judgment, there may be money waiting for you. You do not need to hire anyone to claim it. You can contact the Clerk of Court in the county where the foreclosure took place, ask whether surplus funds exist from your sale, and file a claim directly. The process can take time, but the funds belong to you by law.

And for everyone, the broader lesson is that the foreclosure auction system, for all its complexity, operates on a set of rules that are publicly documented and consistently applied. The investors who succeed in this space are not the ones with the most money or the best connections. They are the ones who take the time to learn the rules, do the research, and understand exactly where every dollar goes before they raise their hand to bid.